Introduction

In this article we will explore the epicurean notions of wellbeing my primary source is book one of Cicero’s De Finibus in which Lucius Torquatus delivers a broad outline of epicurean ethics.

(Lucius Manlius Torquatus was an ancient Roman statesman and military general during the later Roman Republic. Torquatus was an epicurean as revealed in Cicero’s De Finibus written in 45BC which accounted philosophical discourses of Cicero’s younger days. He was friends with Marcus Junius Brutus and the esteemed Roman polymath Marcus Tullius Cicero.)

The epicurean pleasure

‘The chief good, the chief good!’ This phrase was all the rage among the ancient Greek philosophers spoken frequently and argued frequently within and between various philosophical schools. Whatever it was be it an ethical practise or a state of mind, if it promoted the best way of living, wellbeing and outcompeting the other ideas then the idea was deemed as the chief good. Epicureanism has its own conception of what constituted the chief good and so what is its conclusion on what is the chief good? Pleasure or hedonia is the chief good! In epicurean ethics and just like within many schools of philosophy, common words have different meanings or jargons. The epicurean school is no different with its meaning of pleasure. The epicurean incarnation of pleasure is not to be confused with modern hedonism, which is the pursuit towards many numerous forms of sensory gratification as humanly possible; the maximisation of pleasure even to excess. Modern hedonism is closely related to debauchery rather than to its epicurean counterpart.

The epicurean school was often accused of butchering the common terminology of what was meant by pleasure or the hedone; cynically they were accused of taking great pleasure (pun intended) and fondness in schooling others by telling them that they did not understand what Epicurus means by pleasure. Before we look at the epicurean definition of pleasure let’s define pleasure by its colloquial meaning back in ancient times. Who else to define it better for us modern folk other than the mighty man of letters Cicero! Cicero states the definition of pleasure in his day: ‘the universal opinion is that pleasure is a sensation actively stimulating the percipient sense and diffusing over it a certain agreeable feeling.” In other words delightful stimulation of one of the physical senses by which both words of that time, namely the Greek hedone and the Latin voluptas meant. Some trivia, Voluptas was also the name of the Roman goddess of sensual pleasures and is the daughter of Cupid the Roman god of love.

Now to define what Epicurus meant by pleasure and what better definition of epicurean pleasure can there be other than taken from the horse’s mouth? In Epicurus’ letter to Menœceus, Epicurus reveals in the letter his definition of pleasure stated clearer and more luminous than daylight itself that you can’t misunderstand it; unless you were an enemy school attacking Epicureanism by intentionally misrepresenting it.

“When we say, then, that pleasure is the end and aim, we do not mean the pleasures of the prodigal or the pleasures of sensuality, as we are understood to do by some through ignorance, prejudice, or wilful misrepresentation. By pleasure we mean the absence of pain in the body and of trouble in the soul. It is not an unbroken succession of drinking-bouts and of revelry, not sexual lust, not the enjoyment of the fish and other delicacies of a luxurious table, which produce a pleasant life; it is sober reasoning, searching out the grounds of every choice and avoidance, and banishing those beliefs through which the greatest tumults take possession of the soul.”

Our innate avoidance of pain

In epicurean philosophy, all living things seek to avoid pain and pursue pleasure:

“This Epicurus finds in pleasure; pleasure he holds to be the Chief Good, pain the Chief Evil. This he sets out to prove as follows: every animal, as soon as it is born, seeks for pleasure, and delights in it as the Chief Good, while it recoils from pain as the Chief Evil, and so far as possible avoids it. This it does as long as it remains unperverted, at the prompting of Nature’s own unbiased and honest verdict” – Lucius Manlius Torquatus

If I was to argue on behalf of this epicurean concept then I would make this argument. We know that pain exists as a motivation for living organisms to avoid situations that give rise to it. A child learns very quickly not to touch fire ever again after he made contact with a burning candle and felt the burning pain from his blistering hand. Acute Pain warns us of disruptions to the normal workings of the body, whether by means of poison, disease or harm to ensure survival. However, pain that continually ensues is an anathema towards a good quality of life. The only situation you should endure pain is if it allows you to escape a greater pain.

“…men who are so beguiled and demoralised by the charms of the pleasure of the moment, so blinded by desire, that they cannot foresee the pain and trouble that are bound to ensue.”

Having to bear pains on the way in the journey for the pursuit of pleasure is folly to the epicurean view it’s not what we have but what we enjoy constitutes our abundance.

“No one rejects, dislikes or avoids pleasure itself, because it is pleasure, but because those who do not know how to pursue pleasure rationally encounter consequences that are extremely painful”

Sometimes the pursuit of pleasure as the goal we set out for ourselves in whatever endeavour at the beginning, we instead at the end find only pain and not our expectations the pleasure that was pursued; in other words, sh*t happens.

Aponia – the complete absence of pain

“… the greatest pleasure according to us is that which is experienced as a result of the complete removal of pain… When we are released from pain, the mere sensation of complete emancipation and relief from uneasiness is in itself a source of gratification”

And so, the greatest pleasure is that which is experienced as a result of the complete removal of pain. Pain here includes not just bodily pain but also pain of the mind. When we are completely released from pain the sensation of complete emancipation and relief from dissatisfaction is in itself a source of gratification, the take home point here is pain limits our pleasure.

This all becomes clear with examples, suppose you haven’t eaten or drunk anything, not one morsel of food not one drop of water, nothing in two days. You come across some food, simple bread and water and you proceed to eat it. After ingestion, you experience pleasure; greater pleasure than if you would’ve normally have eaten bland bread and simple water without going hungry or thirsty. Why is this? Why are you experiencing this flood of pleasurable sensations? The reason for this flood of pleasurable sensations is because it’s a consequence of the removal of malnutrition and thirst fizzled away after you ingested the bland bread and simple water. It is the removal of pain; the greater the difficulty the more the glory in surmounting it.

“A pleasure is greater if not accompanied by any apprehension of evil”

Epicurean classification of desire

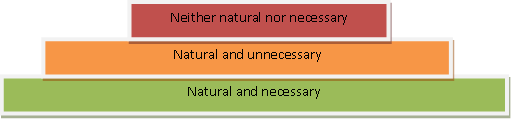

Above, I’ve compiled a simple pyramid of the classes of desires, the concept is from De Finibus, as we go up the pyramid the desires are harder to obtain and become more superfluous.

- The Natural and necessary class are desires gratified with little trouble or expense because they are desires that spring from nature and do no wrong.

- The Natural and unnecessary class are desires, though natural, are superfluous for maintaining a life free from pain.

- The Neither natural nor necessary class are desires that spring from our imaginations and are not required to maintain our health and wellbeing.

It was thought that natural and necessary desires are enough for us to enjoy life. Whilst in contrast, the neither natural nor necessary class of desires being the most superfluous, may in its pursuit result in unintended circumstances resulting in pain.

The Epicurean wise man

The epicurean wise man is outlined by Torquatus near the ending of Book 1 in De Finibus and just like the Buddhists and the Stoics; the Epicureans join them in agreement of the present moment as the true enjoyment.

“For Epicurus thus presents his Wise man who is always happy: his desires are kept within bounds; death he disregards; he has a true conception, untainted by fear, of the Divine nature; he does not hesitate to depart from life, if that would better his condition. Thus equipped he enjoys perpetual pleasure, for there is no moment when the pleasures he experiences do not outbalance the pains; since he remembers the past with gratitude, grasps the present with a full realisation of its pleasantness, and does not rely upon the future; he looks forward to it, but finds his true enjoyment in the present moment“

I gather that freedom from pain in the present moment and the realisation thereof is the chief good.

Further Reading:

De Finibus Bonorum Et Malorum (About the Ends of Goods and Evils)