The stoics were in the habit of reminding their friends through their letters, the students in lecture halls and especially themselves on the certainty of death. Seneca, like all the other stoics, also stressed about being aware of the certainty of death, but what made him special was that he advised we should be economical about how we spend the time we still have living in response to it.

“It is not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it.” – Seneca

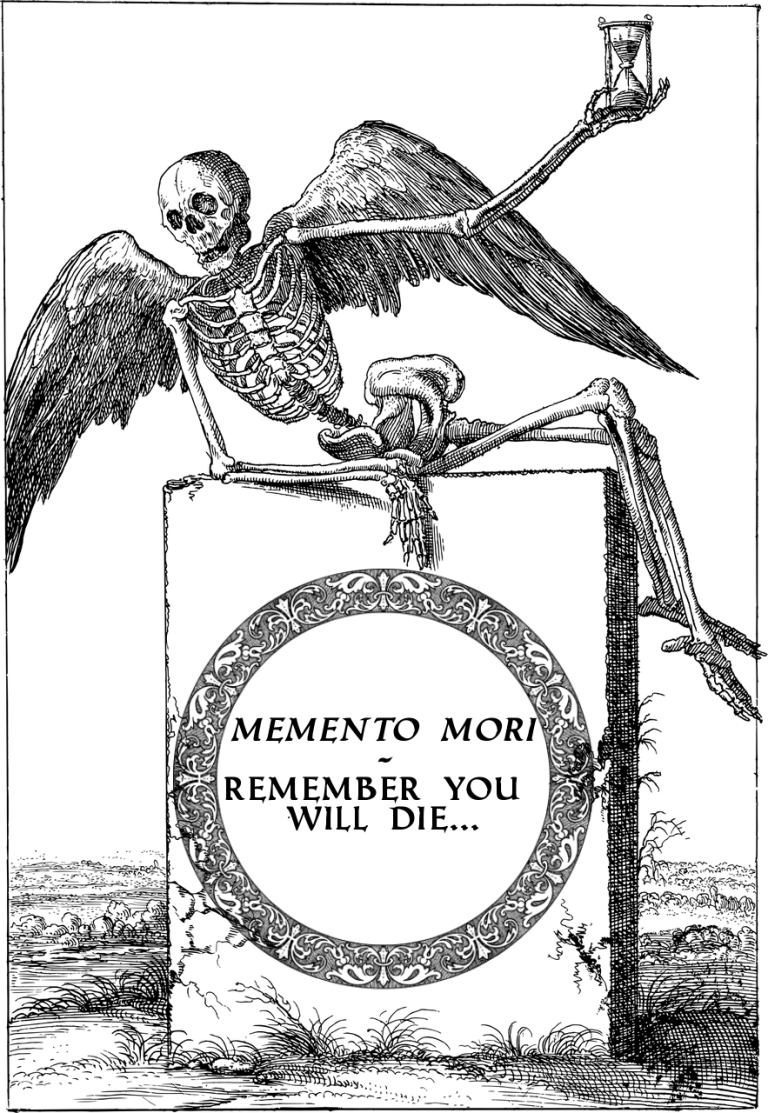

We already covered the certainty of death (memento mori) and now we’ll get into one of the stoic responses to death, on this occasion we will tackle the finitude of life. My main source of inspiration is the best known work in stoicism for answering this, which is Seneca’s ‘On the Shortness of Life’. Of course all the stoics throughout their writings gave a paragraph or two expressing their thoughts on life ticking away – but this time we will focus on Seneca and all the quotes from now on are from him.

Seneca saw his fellow Romans ‘act like immortals’ in pursuing the objects of their desire. His contemporaries already laid out future plans about how to spend their retirements, like lavishing in the world of leisure and giving up public duties – by the way these were plans for decades to come, talk about shooting the gun!.

Thousands of years later nothing has changed, save perhaps the multitude of plans made possible by living in the modern industrial age, people still plan way in advance and are not aware of what could interfere in-between now and a much anticipated plan. In my life, I had a colleague from a previous job many years back who would confidently be making long term plans for holidays abroad; he would say ‘I’m going to Ibiza next year!’ Every time I remember what he said, this quote by Seneca arises in my mind in association with it.

“what guarantee do you have of a longer life? Who will allow your course to proceed as you arrange it?”

When we make plans for a much anticipated experience we certainly prefer to be still living by that time to experience it, but we should be aware the only certainty is uncertainty.

“Counting even yesterday, all past time is lost time; the very day which we are now spending is shared between ourselves and death.”

The Stoics accepted that there’s no guarantee anybody may be alive one year from now, in truth there’s no guarantee anyone will be alive next month, next week, next day and so on. To assume anyone will still be alive on some set date of a future time is to make us vulnerable to disappointment in the eyes of the stoic, because there is no quarter where death may not approach and nobody can foresee how the future will actually play out; we can only guess. So before we enjoy the fruits of life we must be aware of our death and that of others, so as to not be caught out by the unexpected which puts the heaviest load upon our minds.

We’re not getting any younger and as our life continues onward, we continually leave behind a trail of moments spent away into oblivion, only able to be revisited as a simulation in our memories.

“You are living as if destined to live forever; your own frailty never occurs to you; you don’t notice how much time has already passed, but squander it as though you had a full and overflowing supply.”

Seneca argues that we have been given a generous amount of time for us to achieve things, but that time is wasted too much on luxury. We can add distractions as another factor to Seneca’s argument, distractions draw our attention away from the productive activities we are undertaking, like self-improvement. We may not realise that distractions are costing us time and it does not have to be something out there from our environment because distracting thoughts are distractions too!

The majority of people in the modern world live by wage work and with that time and money are bound to one another. Imagine you’re working a job that pays £10 per hour, that wage rate represents how much your time is worth measured in currency; no more, no less. Next imagine you’re paying a visit to the mall to do some shopping and you pass by a shop window that only took a glimpse to see what was behind it to catch your attention. The window displays a product, which you’re considering to buy and it costs £100. Now being a rational consumer, you begin to weigh up the cost and benefit of parting your £100 in cash for that product.

We’ll abruptly stop there and get straight to the point – any product or service you spend money on is the spending away of hours of your time represented by money. If you decide to pay the £100 then that means you are trading the representation of 10 hours of your time, because you had to commit 10 hours working to make that £100. Realise this, we cannot withdraw an additional 60 minutes just like withdrawing £60 out of our cash balance. All time spent is irretrievable as well as the moments that happened within that time frame – time is incorporeal, it is not something that is visible or tangible which can be traded like precious metals in a market.

‘Of all people only those are at leisure who make time for philosophy, only those are really alive. For they not only keep a good watch over their own lifetimes, but they annex every age to their own.’

Spending our efforts in reading and comprehending philosophy… is that not a good investment of our allocated time? Why a good investment of our time? because we are accumulating a store of knowledge and the wisdom of the past. For our effort in attaining that knowledge and wisdom, we have gained something from our use of time, that something we can employ for present or future use and being a fleeting thing like pleasure.

If you prefer to binge watch marathons on Netflix committing many hours each day in the process or playing video games pumping in double to maybe treble figure hours end-to-end, where the only thing accumulating is a save file; that is of course your choice. Should you spend your hours on those activities or any activity for that matter, and after the deed is done develop regrets in feeling you’ve wasted your time. Then be aware in hindsight what made those activities worthy in the first place?

I have seen a number of videos interviewing people on their impending death because they have a terminal disease. A renewed appreciation of life was the response often mentioned and one young cancer patient said: ‘I don’t think cancer is a gift, but it’s an awakening.’ After the realisation sinks in, the noticeable change in one’s behaviour and attitude follows. Feeling that we know for certain that ‘this is it’, that we may not be living in a couple of months – suddenly makes the time we still have valuable, of which Seneca was banging on about.

The bottom line

When we hear that our time is finite and can suddenly be cut short by untimely situations, we may develop this sense of urgency in response to it. But paradoxically in stoicism, when it all comes down to the bottom line, the fundamental thing which makes the good life is our minds which is the real measure of what makes the good life and not the length of time we have spent. Seneca writing to his friend Lucilius, had this to say:

“To have lived long enough depends neither upon our years nor upon our days, but upon our minds.”

We could potentially live until we are very old, but that does not mean that it will be a good life; it could be decades of misery! Time always is running out, young or old does not matter, but the measure of the good life depends on the quality of our minds and the wisdom knowing how to life it well and ensuring it sees to it!