This part is a build up towards the main point: the stoic response to death. So for now there will only be minimal mention of stoicism here.

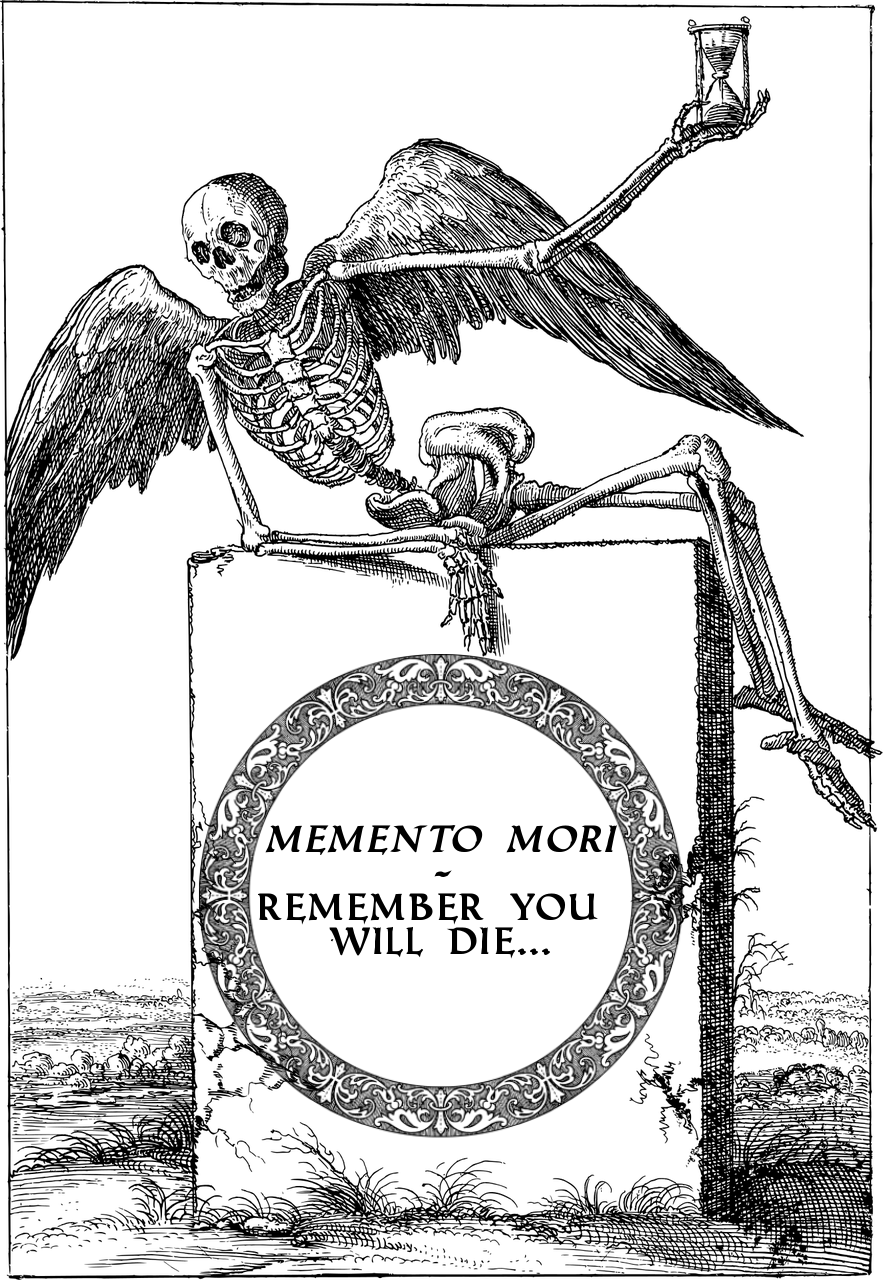

Memento mori is a Latin phrase used as a special personal reminder ensuring us to be aware of the inevitability of death. The reminder has been significant enough to have its own art and jewellery, often in the form of a grimacing skull serving as physical reminders in case we forget. There are memento mori rings which people can fit around their fingers and carry around wherever they go, so that next time working at the office job, tapping away on their workstation keyboards making money for the boss, that grimacing skull wrapped around their finger serves as the physical reminder of mortality.

There’s no better place to find a public reminder of memento mori than visiting the graveyard, in which this popular epitaph comes to mind:

Reader, Behold! As you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I,

As I am now, so you must be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

It’s the wake-up call pointing to inevitable mortality, a message there for everyone to see, the text engraving is in your face and not some abstract concept from a book. What more could you need than the proof lying before you, a grave encasing what was once a person and if one grave isn’t enough look around!

Separation from things cherished

Stoicism urges us to cultivate the awareness that when we die, we will lose everything we have accumulated hitherto in life despite our human exertions in attainting them.

No longer able to interact with our possessions and creature comforts; we’ll even lose that memento mori ring! Rich or poor, noble or peasant, resident or homeless – upon death you’ll either lose much or lose little. Should the wealthy group outlive the paupers, it only means they postpone mortality just so much longer, because it all comes down to the question of who goes first and who goes later.

There’s no guarantee that the projects or jobs we are currently undertaking will see completion, even an article like this – which I’m writing out right now on this keyboard – is not guaranteed to see publication (yet it did huzzah!).

Our soulmate or spouse of whom we may have spent many decades in the company with, who were the recurring figure of our daily routines and always counted on to be there. Who was our ever present accomplice participating in shared moments and the special experiences of our lives – the nostalgia of which could be recorded on photo albums heaped up in the cabinet drawers. There will come a day when one of us will pass away before the other.

Returning after the funeral service, the atmosphere throughout the home is palpably very different, perhaps we notice the quiet or perhaps we find it strange to sit alone in our living room sofa watching evening TV at our regular time. Upon our retiring for bed, we notice the temperature is without the usual warmth given by the metabolism of two people. From our separation results the end of companionship and the beginning of adjusting to a new way of life.

If you’re a grandparent wishing to visit your grandchildren routinely to be there to see how they progress over the years, death is no respecter of our wishes to continue that, should that particular day on which the life processes that sustained your body terminate then in that circumstance, no wish, no matter how strong, will make a difference.

Separation from aversions

“You will find it quite easy to face death if you stop to consider the business you will be leaving and the sort of characters which will no longer contaminate your soul.” – Marcus Aurelius

To only focus on separation from the cherished things is not telling the whole story because upon our death we’ll have nothing to do with our aversions anymore. The things in our life that gave us hassle, stress, pain, anxiety and any other ongoing unpleasant experiences will all come to an abrupt cessation and our needing to deal with them.

Even though the nature of the world is impermanence in general and relationships between people shift like the desert sands in particular. Should we have any unpleasant characters in our lives which circumstance forces us to be with for a chronic amount of time – it cannot persist forever, eventually either you will pass away or the other fellow will.

Youth is no protection against death

The folly of youth believe that for the sole reason they are young, they shall not be grasped by death so early, imagining themselves on their deathbed at age 84 or some other arbitrary old age. This is the error of placing one’s faith on the law of averages – it may be true that the young are less likely to die sooner than the elderly – but there’s no guarantee that one individual youth will outlive someone who’s old. Should they find out that they will die very soon, from whatever reason that may be, the reaction is that of surprise and disbelief – ‘I’m too young to die!’ – because they’ve placed their faith in a belief.

To use youth as the guaranteed reason for shielding against early death is a poor pawn to play in the chess of life, when there are so many ways the life of an individual can be undone. For example, I read a while back of a young doctor in his mid-20s – who was full of promise for a successful medical career – was killed in a tragic skiing accident leaving behind a devastated family and weeping girlfriend.

It can come out of nowhere

It’s in the terms and conditions of life that death can happen anywhere and at anytime and there’s no fixed duration when death will happen.

What’s the typical modern ideal of how a citizen’s life in the industrial world should play out these days? If I’m not mistaken, the outline is like this:

you’re born – you attend school – you attend college or university – get a job (preferably high paying) – get married – get your own house – have children – raise children and work to support the family – continue working, try getting promotion – make sure children get good education and job – become grandparent when children have your grandchildren – retire/collect pension – die.

As was mentioned this way of living the typical modern life is an ideal, but ideals cannot guarantee how the actual reality will play out. Many stages comprise this life formula, but the end can happen on any stage along the way.

Death will always be untimely if we are working towards any goal in life – to illustrate: If after school we plan on further education – college or university – but that plan is thwarted by our death; this makes death untimely, If we finally have our own home and plan on creating a family with our partner but we die before we can do so; this makes death untimely and if we are in the middle of raising children and on the cusp of getting that promotion after decades on the job, but die before that raise; this makes death untimely.

A terminal illness gives us a warning in advance that we may die soon, but for those of us who’re a picture of health there may be no reason to give consideration to the possibility of death, yet we could die from an acute illness. Imagine a scenario where you’ve been hospitalised and are in a critical condition, you find yourself in a ward lying on one of the beds that happens to be not far from a half opened door leading out to the corridor. Just outside that door the doctor is talking to someone about your health situation – unaware that you’re listening in – he says the words “There’s little we can do”, “I’m not sure if he can make it”. In a situation like that, where it cannot get any worse, then it’s a case of either you’ll get better or you’ll die!

As soon as anything is born, the timer starts ticking. When a human baby is born, that person’s journey in living life begins and many experiences await on the way walking through it as a living being responding to the varied stimuli the journey has to offer, but along the way they should pay heed to memento mori for that whole journey is on a one way road towards a terminal end and that is death.

End of preliminary

The ideal stoic attitude in response to death is one of preferred indifference. Does this make our stoic eager to die!? to lift his philosopher’s beard and sever the carotid arteries signalling his end by a messy show of crimson? The answer is a resounding NO! – but he recognises that as a consequence of having the privilege of being born, he is destined to die. The stoic attitude resists emotional passion and favours reasonable assessment.

There is no single stoic response to death, but in fact there are many which come in the form of various, reasons, arguments and observations. The stoics perceived death from many angles which opens up new, alternative ways for us to look at it. How someone would react to these teachings depends on their disposition, but the intent is to challenge the initial impressions and mental perturbations that commonly arise when thinking about the death of oneself and others.

This is where we will depart from this preliminary and move on to the stoic responses to death…