Cato continues his pep talk on why old age should not be looked upon as a burden:

“I no longer wish for the strength of youth – that was the second objection to growing older we listed – any more than when I was a young man I desired the strength of a bull or an elephant.”

Cato’s declaration here is one of non-attachment and equanimity, he does not grasp at the loss of his youthful strength. Instead Cato recommended that we be utilitarians in whatever stage we are in the aging process. Moreover, Cato’s indifference to infirmity in old age is in line with his keeping true to his surrender to nature and fate as they unfold.

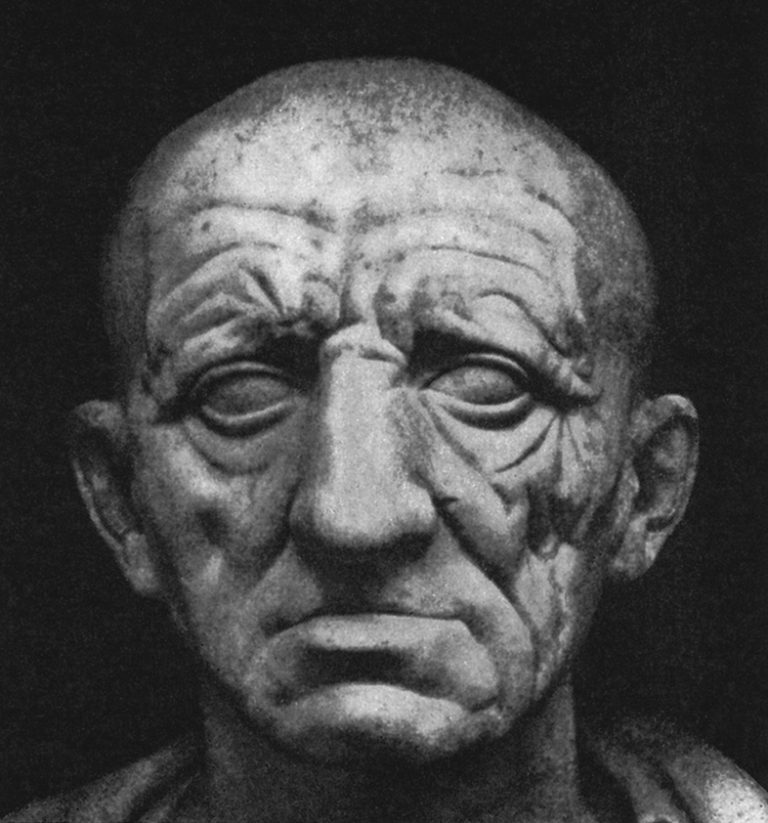

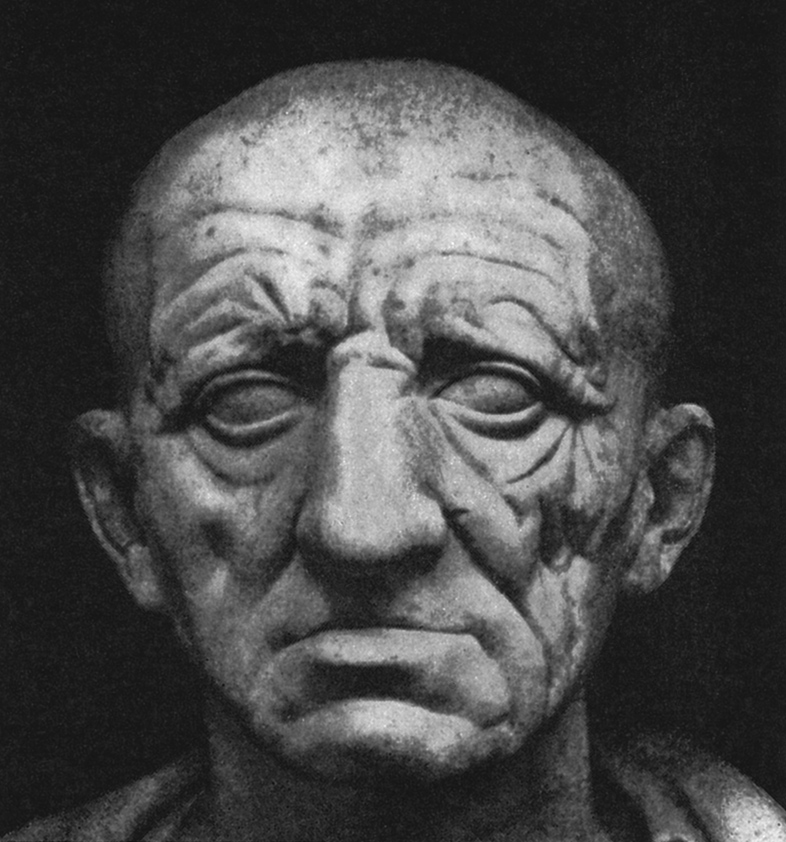

The Rise and Fall of Milo of Croton

In the 6th century BC in southern Italy there was Croton, a Greek colony known for producing great athletes. The most notable of them was the wrestler, Milo of Croton. Milo was a paragon of strength, reported to carrying an adult ox on his shoulders as a method of strength training. He participated in the Olympic games and achieved a winning streak of six times.

Cato reports a story about Milo who was an old man at the time:

“One day when as an old man he was watching the young athletes training on the racecourse, he reportedly looked down at his own muscles and wept saying: and now these are dead.”

Upon hearing this story Cato found it to be pitiful and foolish saying of Milo:

“But not as dead as you, foolish man! For your fame never came from yourself, only from the strength of your sides and arms”

In analysing this event, Milo compared his muscles to the youthful athletes. He realised that his muscles have atrophied because of his old age. He grieves because he is an old man who’s lost the physique of his youth while he sees before him young athletic men in their prime. Now isn’t this an archetypal scenario of ‘how the mighty have fallen’ given Milo’s epic background as famous athlete to old man spectator looking on from the side lines.

Pep talking Milo of Croton

If I could have imparted my perspective to Milo at that time I would’ve told him this:

‘Milo, because of the passage of time your body has grown old. The passage of time is a consequence of the laws of physics; it is nature’s universal will. The aging of any living organism will continue throughout its lifespan and provided it lives long enough will become old in its own lifetime. The Epicureans and the Stoics knew full well that all things in the universe tend towards disorder. The ways in which things succumb to disorder are manifold, the very racecourse your standing on will itself degrade one day into a ruin. Do you think that this very racecourse is exempt from the abrasive disorder which perils the whole universe itself!

*Milo ponders for a moment and then turns his head away, his attention directed towards the youths again*

There you go again, comparing yourself to the youth! If you’ve grown old then hasn’t it occurred to you that they will too? Think in this way Milo, when you were a young athlete at the top of your game, all those decades ago, it may have been you on that racecourse and some other old man sitting here. With that very logic, those youths you see before you will have their turn in becoming the old men viewing other youthful athletes on the racecourse in decades to come. This will go on and on until there is no racetrack anymore to set the scene for this pitiful scenario!

Yes they’re performing their athletics with great finesses! Yes Milo they are young, yet how long can that go on for? Do you suppose those youths dive into such depths of arrogance as to expect that the universe’s natural tendency towards disorder will be put aside just for them!? An Adonis like body is only temporary, health is only temporary, they can only enjoy while it lasts!

Is your only value in athletics Milo? What about pursuing something different; is there any room for that? What about running on the racecourse of the mind? You could write a treatise on athletics, your own autobiography or how about a book detailing your peculiar strength training method and how it’s served you over the years; now there’s a gym you can join!’

Cato being a man who lives for the mind had this to say:

“They say that Milo walked the length of the Olympic stadium carrying an ox on his shoulders. But what would you prefer to be given, the physical strength of Milo or the mental power of Pythagoras?”

The elderly as teachers

This passage feels like it should be placed in the first objection:

“Surely we must agree that old people at least have the strength to teach the young and prepare them for the many duties of life. What responsibility could be more honourable than this?”

Cato noted Scipio’s two grandfathers, Lucius Aemilius and Publius Africanus who were often accompanied by crowds of noble young people. Hinting at what was said, they probably had much to teach the noble youth about the world. Despite if the body is not as strong as it used to be, the grandfathers were shown to enjoy the company of youth as teachers and role models. A consequence of a mind that has undergone development in wisdom, knowledge, sound judgement and experience.

Our bodily condition come old age depends on our youthful lifestyle

Now here’s an argument that is against the objection that ONLY old age weakens the body.

“The excesses of youth are more often to blame for the loss of bodily strength than old age. A wanton and wasteful youth yields to old age a worn-out body”

This is an interesting perspective Cato gives us, instead of isolating the latter stages of our lives and just focusing on that. Cato introduces the perspective from a developmental outlook, that to become old we must first go through youth and it is the quality of our youth and how that played out that is a crucial factor in determining the quality of our old age. Cato argues later that if we practise self-control and take care of our bodies by exercise we can preserve some of our original vigour even when we grow old.

Cato does not equate old age with poor health in fact he separates the two depending on the individual and their lifestyle. He notes that even the young cannot escape infirmity.

As I read through this work I’ve noticed a pattern in Cato’s style of argument. In order to give substance to his arguments he often points to other individuals in antiquity (often notable historical figures) who in their old age have defied the objections popularly used against it. Cato points to the Persian king, Cyrus the great, for example:

“The elderly Cyrus, according to Xenophon, declared as an old man on his deathbed that he had never felt less vigorous in his later years than as a young man.”

Now Cato, being 84 years old in this dialogue, admits that he wished he could make the same boast as Cyrus the Great. He admits he no longer has the same energy as when he was a young soldier serving in the Punic wars, ‘but’ he said ‘nonetheless, as you can plainly see, old age has not unnerved or shattered me.’ Neither his friends nor the Senate have found his strength lacking.

The authentically Stoic part

Cato continues on about bodily strength, and it’s in this passage here being a real gem of a statement because it feels so characteristically Stoic:

“In short, enjoy the blessing of bodily strength while you have it, but don’t mourn when it passes away, any more than a young man should lament the end of boyhood or a mature man the passing of youth”

This passage is indirectly referring to Milo, but the last portion of this advice is profound because what is suggested here is that we adopt equanimity towards all the periods of our aging; from cot to elder.

We must say to ourselves, ‘I’ve past my toddlerhood, I’ve past my childhood, I’ve past my adolescence, I’ve past my young adult years, I’ve past my middle adult years and now I’ve reached old age and I do not miss the previous periods in my life any more than the current period; because I refuse to privilege on above the other.’

It’s all part of the life cycle, just as an acorn has the potential to become an oak tree, so does a baby human being have the potential to become an elderly human being. However unlike the acorn the baby human, being an animal, possesses a most judgemental nervous system that has the potential to make the quality of their lives a living hell! Instead, if we are going to maintain peace of mind in our winter years we must be as indifferent to aging as like that of an oak tree. For instance, the Bowthrope oak in England is over 1000 years old!

“The course of life cannot change. Nature has but a single path and you travel it only once.”