After the controversial fallout of Anti-Seneca, our philosopher physician gives his final caper in his writing of the Preliminary Discourse which was included in his Philosophical Works published in 1750. Since this was the last of his works, for he died a year later, it can be considered to be his most mature espousal of his materialist philosophy and defence of it.

Ann Thomson the editor of Machine Man and Other Writings published by Cambridge University Press summarises this work:

“His main aim in the Preliminary Discourse is thus both to reaffirm his materialism and to show that his philosophy is not dangerous, because the object of philosophy is totally separate from that of morality and religion; philosophy is concerned with the search for truth, while the aim of morality and religion is to protect society.”

This passage here is the best citation for La Mettrie’s distinction between philosophy and religion/politics:

“The morality of nature or of philosophy is thus as different from that of religion and politics – the mother of both – as nature is from art. They are so diametrically opposed that they turn their back on one another. What should we deduce, except that philosophy is absolutely irreconcilable with morality, religion and politics, which are its triumphant rivals in society, only to be shamefully humiliated in the solitude of the study and by the light of reason’s torch. They are humiliated above all by precisely those vain efforts that so many clever people have made to reconcile them”

This work was not just an apologism for his materialist philosophy but was also advocating for the unrestricted freedom for philosophical ideas to be discussed in the marketplace of ideas.

As is the habit of my reviews I highlight the noteworthy in block quotes and talk about the key themes of the work often giving a neutral commentary unless I do have a critique to share.

Philosophy vs Morality, Religion and Politics

Right at the beginning the author shows us his intentions, he says ‘I intend to prove that, however much philosophy contradicts morality and religion, not only can it not destroy these two bonds of society, as is commonly thought, but it can only tighten and strengthen them more and more’

La Mettrie shortly after proclaims that philosophy is subject to nature, ‘as a daughter is to her mother.’ In La Mettrie’s eyes philosophy has more to do with nature than morality and religion:

“After following man step by step and seeing what he inherits from his forefathers, his different ages, his passions, his illnesses and his structure compared to that of other animals, you will agree that faith alone leads us to belief in a supreme being.”

On this sentence above he got to this conclusion by two things being prerequisite:

1) He was an experienced physician, note on how he touched about illness and comparative anatomy.

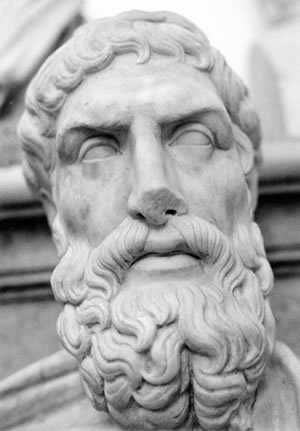

2) He was a philosopher, who was much influenced by Epicureanism and materialist philosophy in general.

Philosophy in general and materialist philosophy in particular has often, time and time again throughout history, drawn our attention away from the theological narratives and away from the resounding voices of the charismatic preacher echoing throughout the church. It leads us down from the whole lofty mire of the teleological and theological cloud to the physical ground of the earthly existence that is with us always. Philosophy shows us this earthly existence and lo, we humbly see surrounding us only ‘eternal matter and forms perpetually taking each other’s place and perishing, you will admit in embarrassment that all animated bodies are destined for complete destruction. And finally, once the trunk of the moral system has been totally uprooted by philosophy, all the efforts made to reconcile philosophy and morality, theology and reason, will appear trivial and futile’

In the dog eat dog world of nature, early man was in his technologically naked state, the frail human being by himself cannot hope to best the beast in a state of nature. The solution was cooperation in large numbers so that the humans get a fighting chance in surviving. It is here, when people started living together, society was established and there was a need to formulate a system of political morality to safeguard the cohesiveness of said society. First was the rule of law and its institutions but man being an unruly animal required a second form of law that of religion. La Mettrie explains to us briefly the rise of religion by wise men worthy of leading others who called upon religion as the second enforcer to the rule of law which was seen as: ‘too cold and rational to be able to acquire absolute authority over the impetuous imagination of a turbulent and superficial populace. Religion appeared, its eyes covered with a sacred blindfold and soon it was surrounded by all that multitude who listen in open-mouthed amazement to the wonders for which they yearn; and oh miracle! the less they understand these wonders, the more easily they are subdued by them‘

‘the less they understand these wonders, the more easily they are subdued by them’ This statement leads me to think of deepities which are profound statements superficially but upon closer scrutiny are false or meaningless.

Moreover on this, anecdotes are stories and tales that communicate ideas to the listener. Stories are entertaining and more engaging than that of a law tome. Religion has this advantage over law as religion is full of anecdotes and stories often with a moral teaching able to be communicated to adults and children ‘who listen in open-mouthed amazement to the wonders’. Back in those days before the industrial revolution people had not the time nor the connections or money to delve into moral philosophy or law. Religious moral teachings however, is aimed at the masses making it far more accessible and diffuse because it was a public force with its own sermons, street preachers and pamphlets and not something confined to a private study like law or moral philosophy.

La Mettrie contrasts two types of morality, religious and natural morality:

“Listen to religious morality: it will order you imperiously to prevail over yourself, deciding without hesitation that nothing is easier and that ‘to be virtuous is only a question of will power’. Lend an ear to nature’s morality; it will invite you to follow your desires, your loves and whatever gives you pleasure, or rather you will already have followed its advice. Ah! the pleasure it inspires makes us feel clearly, with no need for such superfluous reasoning, that this pleasure is the only way for us to be happy.”

La Mettrie critiques religious morality further saying that it encourages us to go against natural morality, in other words, to ‘stiffen ourselves, rise up against it’ and we must, despite ourselves, sacrifice our authenticity and be like (presumably) other pious people and conform. However, you can be virtuous without having to follow a religious morality. It’s passages like this that probably led the materialists in La Mettrie’s camp to distance themselves from him.

On Law and Politics

“The Philosopher concentrates on what seems to him to be true or false, whatever the consequences; the legislator, scarcely concerned with the truth and perhaps even (through lack of philosophy, as we shall see) afraid that it might come to light, deals only with what is just or unjust, with moral good and evil”

Imagine this scenario, a criminal who’s been charged with murder in a courtroom of law pleading his own defence states in a straight face and serious tone: ‘I have not murdered him your honour I have merely re-arranged his atoms! I committed the deed because my being is subservient to the laws of physics and the prior configuration of the universe, I had no free will’ The naturalist philosopher who views the world in only its physicality gives an agreement to the statement, then we have a determinist philosopher also in agreement who argues that he was fated to commit the crime because nothing has free will. We philosophers are a funny lot you know, looking beyond the hill of moral judgements and into the vast metaphysical vistas. Anyways, the legislators or judges are not interested in any of that because they are very different to that of the philosopher. They uphold only their functional roles in society for the purpose in delivering justice on to the murderer.

Philosophy does not seek to eliminate morality nor to break the society’s bonds. Instead it gives judgements about morality without becoming morality. If we had to talk about philosophy having its own ‘morality’ it would be nothing other than getting at the truth. Philosophy is monogamous, its only love is truth. La Mettrie viewed anything that is a part of nature should be called truth and whatever is not in nature, whatever is contradicted by observation and experiment should be described as false.

Paradoxically, because philosophy’s sphere of inquiry covers all fields and subjects it is able to contribute to morality without enforcing it or becoming it as was mentioned. The reason, they do not harm each other in any way is because their objects have nothing in common; they are as opposed and distant to one another as East and West.

The same goes for politics. La Mettrie says ‘A contradiction between principles with such diverse natures as those of philosophy and politics – principles whose aims and objects are essentially different does not at all imply that either refutes or destroys the other.’

Politics engages with society at large arguing for what direction it should go, what is best for it. With philosophy it is not just constrained by society, its quest for truth goes well beyond society into the realms of physics and metaphysics through the employ of argument and method. Both Philosophy and politics, these fields, should they ever influence one or the other can only do so indirectly.

He says that philosophical meditations ‘cannot corrupt or poison the practise of society’ I agree, in the sense that philosophical ideas and thoughts in themselves cannot in one jot affect society unless if they are legislated by the state; from the top to the bottom or in the volatile times of revolution by the masses from the bottom to the top!

Odds stacked against philosophy

He sharply changes the subject and aims at his favourite polemical targets; the priests:

“Priests hold forth and enflame people’s minds with magnificent promises worthy of filling out an eloquent sermon; they prove whatever they declare without bothering to reason, and they want us to put our trust in God knows what apocryphal authorities. Their thunder is ready to strike and pulverise whoever is reasonable enough not to believe blindly whatever shocks reason most.”

Throughout the work the recurring themes are the following questions. How is freedom of thought and expression a danger? How is agreeing to what is true harmful? For how can reasoning be dangerous when it has never produced fanatics, sects or even theologians?

“However much the materialists may prove that man is nothing but a machine, the people will never believe it. The same instinct which makes them cling to life gives them enough vanity to believe their souls immortal, and they are too unreasonable and too ignorant ever to ignore that vanity… Thus all our writings are only fairytales in the eyes of the masses, and superfluous reasoning in the eyes of those who are not ready to receive their germs; and for those that are, our hypotheses likewise present no danger.”

La Mettrie was not happy with the overall majority of the population not caring one iota about philosophy, not bothering to study it and in the cases when they did endeavour to study it only to call it bollocks. Instead they were content with religion thinking they need not travel further beyond that. Here in one passage he laments on the inability of men choosing not to revise their principles; he’s calling them stubborn in other words!

“Each man is so strongly convinced of the truth of the principles with which he has been filled and even gorged during his childhood, and his self-respect depends so much on maintaining them without faltering, that even were I as determined as I am indifferent, I could not, even with all of Cicero’s eloquence, convince anyone that he was wrong. The reason is simple. What a philosopher considers to be clear and proven is obscure and uncertain, or rather untrue, for those who are not philosophers, particularly if they are not made to become philosophers.”

Well that one principle, which be inoculated to the child during that critical time of development, will, among all the other principles, become the most important and treasured one. Especially if these ideas are bound with ‘his self-respect’ then he will doubly so be convinced of their validity because a large amount of emotional investment has been poured into it.

He turns the tables by asking if religion, in this case Christianity, has made us any more virtuous?

“Since polytheism was abolished by law have we become more honest?… would Christianity have made Cato the Censor less stern and ferocious, or Cato the Younger less virtuous, or Cicero a less excellent citizen, etc? In short, do we have any more virtue than the pagans? No, and they had no less religion then we.”

Society always had those deemed as misfits and saints but I’m not going to give absolute moral judgements. Who is right or wrong depends on who has treated you wrongly or rightly. The philosopher physician was also moral nihilist, rejecting any notion of an absolute objective morality

“Nothing is absolutely just, nothing absolutely unjust. There is no true equity, there are no absolute vices, no absolute greatness and no absolute crimes.”

Simply being a philosopher or an atheist philosopher in this case does not make one equated to fanaticism no! If we have to play the game of who is a fanatic or not then the fanatics are ‘those monsters vomited forth from the depths of monasteries by blind superstition, a hundred times more dangerous.’ than the philosopher drafting his works within the study. He thinks a society composed only of philosophical atheists would survive much better than a society of theologians because the latter society would. Though following immediately after he was quick in denying advocacy of atheism saying he was examining all of this from the perspective of a ‘disinterested physician’. Judging from reading his writings I think the ship for monsieur Mettrie being discounting from the ranks of the atheists has sailed. He valued the patriots of his country more than theologians:

‘If I were king I would lower my guard on those whose patriotic hearts could provide me with a guard, while I would double it on the others whose prejudices are their first kings.’

La Mettie’s introspection

He talks about himself in his approach to daily life as being compartmentalised. His private and public life he admitted to behaving very differently in. In private, within his study he argues and writes philosophy, not to moralise, but for what he considers to be true. When he finds himself in public, in regards to society at large he never orates philosophy to the great masses because to do so would be a wasted effort, he laments that the whole world is not peopled with inhabitants whose behaviour is governed by reason; his attitude towards the general public is that of pessimism. Philosophy was not made for the masses, in his own words, conversing philosophy to the ‘vile herd’ would be comparable to this: ‘To give a great remedy to a patient who is completely beyond all help is to dishonour it, and to discuss the august science of objects with those who are not initiated into its mysteries, who have eyes but do not see and ears but do not hear, is to profane and prostitute it.’

Just as medicine treats the body; philosophy treats the ‘ the laws, the mind, the heart, the soul etc.’ In short, philosophy ‘rules the art of thinking by means of the order which it puts into our ideas.’ And because of that philosophy interferes with all fields everywhere, jurisprudence, morality, metaphysics, rhetoric, religion etc. ‘philosophy. Without it, without the order that it puts into one’s ideas, Cicero’s eloquence would perhaps have been in vain; all those splendid speeches that made crime turn pale, virtue triumph and Verres, Catilina, etc. quake, and all those masterpieces of the art of speaking would not have gained control over the minds of the while Roman Senate and come down to us.’

Far from being dangerous to society, philosophy, he said, should be viewed as a benefit. Philosophy does not have to be confined to the study but its tools can be used to aid the public for its good. Those that hold the helm of state would benefit themselves and the larger society from philosophy; it certainly benefited Marcus Aurelius the philosopher emperor of Rome. La Mettrie on the one hand, desired the ruling class to be at least a ‘bit philosophical’; and in the other hand, he believed they cannot be philosophical enough! If however the princes and ministers should become philosophical then they can recognise and combat their flaws in reasoning and their prejudices for the benefit of the French nation.

Conclusion

“We applaud your laws, your morals and even your religion, almost as much as we applaud your gallows and your scaffolds.”

Science is a method employed for discovering how the world works, it’s conclusion is experiment and data and not by the whims of ideology or morals; however the discoveries and tools of science can be employed and used for the promotion and advancement of an ideology or moral system like politics and religion. It’s the same with philosophy, its tools such as the Socratic method can help filter out contradictions in ideas by an interrogative inquiry. The tools and methods of philosophy can be utilised to promote and advance any position you can think of be it good or evil but the tools and the methods in themselves have no allegiances.

In a way, La Mettrie was the French Socrates of his time, he believed philosophical inquiry and arguments should be directed at everything, be it religious, societal or natural; all for the purpose of getting at the truth or at least closer towards it. For this he faced exile from multiple countries and the public burning of his works. Despite all of that, he still pressed on vigorously writing as if he were alone in the universe because he was a man of conviction and indifferent about being labelled negatively.

Since the time when the art of reasoning appeared and shortly after philosophical systems were learned, battle lines have been drawn. Those that argued for divinity, mind-body dualism, karma, immortal souls and even the mind as the source of reality were called idealists. Those that argued for atheism, monism (anti-dualism), the brain as the seat of consciousness and physical reality as primary overall were called materialists or naturalists.

La Mettrie was of the latter; a materialist. A materialist philosopher in a sea of idealists who were worried about the written contents engraved by Monsieur Metrrie’s pen. It was so bad that his fellow countrymen exiled him for it. I’d say the reason why La Mettrie’s philosophy was looked upon as a threat to the stability of society at that time was because the ideas espoused by him contradicted the ruling hegemony and zeitgeist. If only he could see how the tides of naturalist philosophy has stretched even further today, he would’ve taken great pleasure in knowing that the grief he went through was not all in vain.

“A philosopher must write with noble daring or expect to crawl like those who are not philosophers”