“Thus the world is not to be identified with any particular substance, but rather with an ongoing process governed by a law of change.”

— Heraclitus (source)

This insight captures the essence of Heraclitus’ metaphysics: the universe is not a fixed being but a becoming—a ceaseless unfolding. Nietzsche would certainly have approved. For Heraclitus, reality is not composed of stable elements, but of ongoing flux. Ice, for instance, is static, defined by form and rigidity; but fire, his central metaphor for the cosmos, is not a substance at all. It is a process—restless, consuming, renewing, in perpetual motion. Fire becomes his image for the world because it embodies change itself.

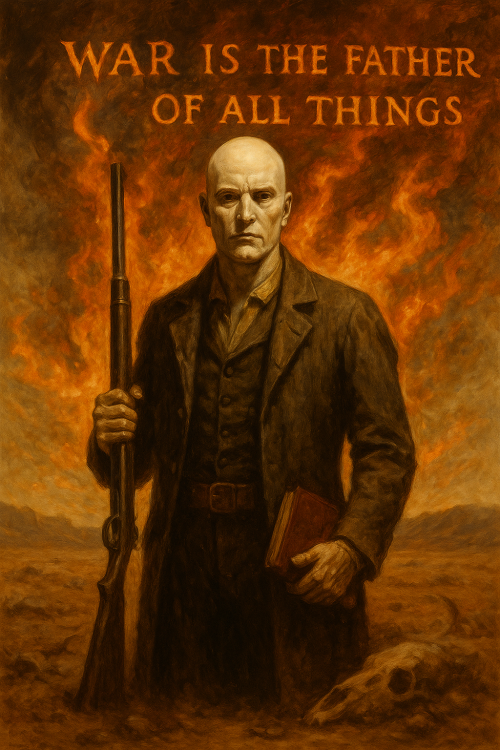

Heraclitus’ famous dictum—“War is the father of all things”—is often misunderstood. It should not be read as a celebration of literal warfare and bloodshed. Instead, “war,” or more precisely strife (eris), refers to universal opposition as the fundamental structure of reality. In Heraclitus’ dialectic, conflict is not mere destruction—it is creation. All things arise from the tension between opposites: life and death, waking and sleeping, hunger and satiety. Harmony is not the absence of conflict, but its outcome.

To avoid confusion, it is better to think of Heraclitus’ “war” as cosmic strife—not military violence. The word “war” today evokes images of cacophonous armed formations, flags, and slaughter. But Heraclitus’ war is ontological. It is the conflict within all things, and between all things.

“We must know that war is common to all and strife is justice, and that all things come into being and pass away through strife and necessity.”

— Heraclitus

This passage redefines justice—not as peace or fairness in the moral sense—but as the equilibrium that emerges from opposing forces. Strife is not a deviation from order. It is order. It is the very foundation of being.

Another well-known Heraclitean image makes this clear:

“Upon those who step into the same rivers, different and again different waters flow.”

The river remains the same in name, but its contents are always changing. Identity, in Heraclitus’ cosmos, is not sameness, but persistence through transformation.

Judge Holden The God of War

This dialectical worldview—where nothing is static and all arises from conflict—finds a disturbing modern echo in Judge Holden, the enigmatic antagonist of Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. Among the Judge’s many infamous pronouncements:

“It makes no difference what men think of war,” said the judge. “War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here.”

Holden, like Heraclitus, sees war not as a temporary aberration, but as the primal condition of existence. For him, peace does not extinguish war—it merely conceals it. War is eternal, impersonal, and inescapable. It is not just something men do; it is what the world is.

“War is the ultimate game because war is at last a forcing of the unity of existence. War is god.” — Judge Holden

Where Heraclitus sees strife as the motor of becoming, Holden radicalises this view. For him, war is not a principle of reality—it is the principle. In both thinkers, however, we find a cosmos governed not by stasis or moral law, but by energy, transformation, and necessity. The world is not a sanctuary—it is a fire.

This is what links Heraclitus and the Judge: their shared vision of a universe in which conflict is primary, and peace is provisional. There is no eternal resting place, no fixed form, no lasting tranquillity. Only the constant churn of fire, change, entropy, and death—the ceaseless dialectic of being.

Europe’s “Long Peace” and the Illusion of Stability

Some in the West may assume that our societies have outgrown violence—that history has turned a page, and we now live in an era where peace is permanent and war is obsolete. The grand narratives of progress and modernity suggest that conflict is a relic of the past, and the only “war” left is the economic rat race. But this belief is dangerously naïve.

Take Europe as a case study. Since 1945, historians and political scientists have described the post-war period as a “Long Peace”—a historical anomaly when compared to the centuries of near-continuous European warfare, from the Thirty Years’ War to the Napoleonic Wars, to the devastation of two world wars.

But is this truly peace—or simply contained conflict?

The post-war peace in Europe has been sustained by a web of treaties, institutions, deterrents, and economic ties. The European Union, NATO, and the memory of destruction have all contributed. But none of this means war has vanished. Rather, war has slept—hidden, constrained, but not eradicated.

And it has returned.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 shattered the illusion of irreversible peace. Old fault lines reappeared. NATO rearmed. Borders were militarised. Cold War instincts awoke from dormancy. The war did not arrive in Europe—it reemerged. We have a simple slogan you can quote to sum this up:

“When there is no war, war lies sleeping.”

This reality affirms both Heraclitus and Holden: peace and war are not binaries, but interdependent forces in tension. War is not defeated by peace—it is only postponed. What unites Heraclitus and Judge Holden is their vision of a dialectical universe, forged in opposition. In such a cosmos, conflict is not aberration—it is the condition of existence. Whether it is called strife, fire, or war, the force that governs the world is one of transformation through tension.

Europe’s “Long Peace” may one day be viewed not as the end of war, but as its intermission.

Heraclitus said: “Strife is justice.”

Judge Holden said: “War is god.”

Both, in their own way, teach us the same thing: that peace is not the end of history—only a pause in its fire.