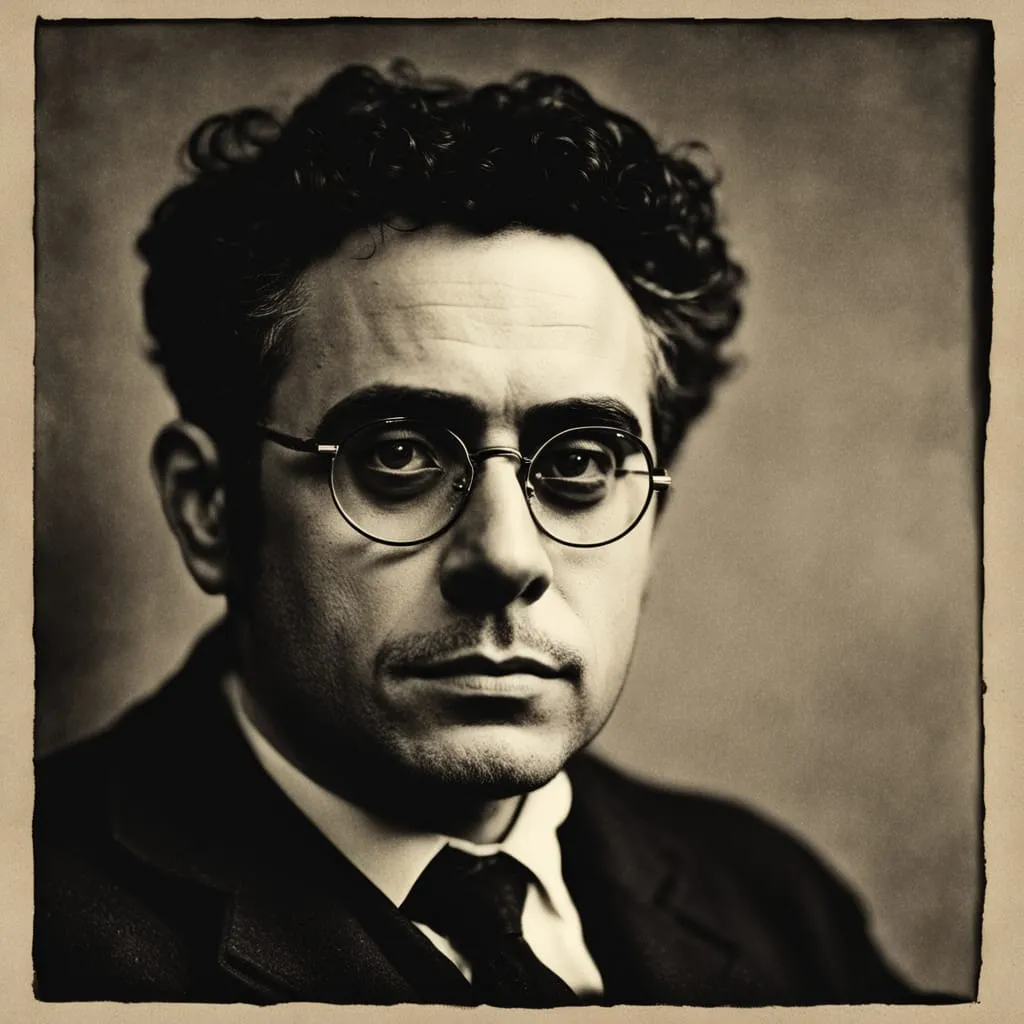

I’ve spent a good deal of time digesting Antonio Gramsci’s writings this year, the Italian marxist famous for his writing his Prison Notebooks while locked up in Mussolini’s prison. Areas of particular interest to me are his ideas of cultural hegemony and civil society. Introspectively, the ideas read in books rub off on you—they equip the mind with new tools to decode the world. These thoughts have an awareness-raising effect, revealing aspects of reality that previously passed unnoticed. It’s a bit like the famous scene in They Live, where Nada (played by Roddy Piper) puts on a pair of sunglasses capable of showing the world the way it truly is. But in this case, the lens is Gramsci’s theory of cultural hegemony—a framework for understanding how power operates as much through consent as it does through coercion.

Gramsci teaches us that the most enduring form of power is not imposed with guns or batons, but subtly exercised through the institutions that surround us—schools, media, churches, and even families. The UK today is a battleground of ideological conflict, where various political and cultural forces compete to establish and maintain dominance in civil society.

Take the example of education. Universities are often seen as bastions of progressive thought. A 2021 report from the Higher Education Policy Institute found that around 50% of UK academics identify as left-leaning, compared to just 15% who are right-leaning. This imbalance may shape curricula, discourse, and student culture. But this ideological contest doesn’t stop at universities. Schools are no different—in fact, they are perhaps an even more strategic space in the battle for hegemony.

But here’s the inspiration in my experience that got me writing this article. As part of my job, I remember visiting a British primary school, and what greeted me as I turned the corner into the foyer was a display that seemed, at first, entirely innocent. A large board stood prominently against the wall, its background a rich navy blue, bordered with bright yellow scalloped trim—a deliberate mimicry of the Ukrainian flag. Pinned across the surface were several A4 drawings in marker and crayon, each showing hearts, doves, and handwritten messages like “Help Ukraine!” and “Support them!” At the centre was a large, bold heart enclosing the word Ukraine, rendered in the national colours.

It made me pause. Are these the genuine political expressions of young children? Or are they reflections of an institutional narrative handed down by adults on behalf of the dominant culture? One can almost hear the coaxing tones of the classroom: “Come on, everyone! Let’s make posters to show our support for Ukraine!” In such a formative and impressionable space, the line between civic education and ideological conditioning begins to blur.

Gramsci reminds us that the ruling class’s most advantageous arrangement is to secure consent from the masses—not through overt force, but by embedding their worldview into everyday life. And what easier demographic to shape than primary school children? If you can win their moral and emotional alignment early, you can naturalise your political position before it’s ever consciously questioned.

This kind of soft propaganda—whether for war, nationhood, or international alliances—is precisely what Gramsci warned about. He challenges the idea that the state is purely a mechanism of coercion. Instead, he argues that all states aim to construct a moral and intellectual order. They seek to shape people’s beliefs, values, and behaviours in ways that uphold the dominant social structure. That includes fostering the perception of certain conflicts—such as the war in Ukraine—as clear-cut moral battles, leaving little space for critical thinking or dissent, especially among the young.

Support for Ukraine in primary schools is not, in itself, the issue. But it is a symptom of a wider phenomenon: the normalisation of political alignment through cultural means. These are not simply the spontaneous ideas of children, but the ideas of the ruling class writ large, dressed in crayons and glitter. Gramsci helps us to see that such displays, however well-intentioned, are rarely neutral.

To be clear, the point isn’t to single out support for Ukraine as uniquely propagandistic. The point is to observe how institutions we consider apolitical—like schools—play a key role in reproducing dominant ideologies. That’s cultural hegemony in action.