“How many in whose company I came into the world are gone away already!”

— Meditations, book 6, 56.

I can imagine Marcus Aurelius writing these words while encamped with his army along the frontiers of the Roman Empire. The second century was marked by plague, war, and political unrest, and Marcus was never far from reminders of human frailty. Around him soldiers fell in battle, friends and advisors died of illness, and news of deaths in Rome would have reached him constantly. For an emperor surrounded by both grandeur and decay, this was no abstract exercise — he was taking stock of a world where every companion of his youth, every contemporary who once shared the stage of life with him, was already vanishing. His reflection is at once personal and universal: the ranks beside us grow thinner with each passing year, until the day we too are counted among the absent.

Marcus is a man tuned into the existential experience of living in a world of constant change and impermanence. When our space of awareness flickers to life for the first time onwards after our birth, the world is already prefigured, already so full of things and ideas. And in particular, it’s filled with humanity that preceded us historically—some already passed away and some older having been born before us. As Marcus observes, those we entered life alongside have already begun to depart, reminding us that time does not hesitate, nor does it grant exceptions. Each moment we live is at once shared with others and slipping irretrievably into the past. This is the human condition: we are born into a heraclitian stream already flowing, joining companions along the way, only to watch them vanish downstream one by one until it is our turn.

After I was born and as I grew older, I came to know impermanence, as we all must. It first appears quietly — in toys abandoned, in friends who drift away, in the sudden realisation that yesterday is unreachable. Later it comes more sharply, in farewells, in the greying of parents, in the empty chairs of those who once watched telly with us. Impermanence is not a discovery of philosophy but of living itself, and it spares no one.

I first came to know impermanence as a child when my parents went abroad on holiday and left me at my grandparents’ house. I remember the small room where I slept, the sound of their voices drifting down the hallway at night. Now decades have passed, and those voices are gone. My uncle owns the house and rents it out to somebody else, who likely sleeps in that very room, unaware of the memories it holds for me. When I was young, I had grandparents; now I have none. More recently, I learned that a friend’s father has only months to live. These reminders arrive unbidden, but they are constant: all things pass, and all generations vanish in turn.

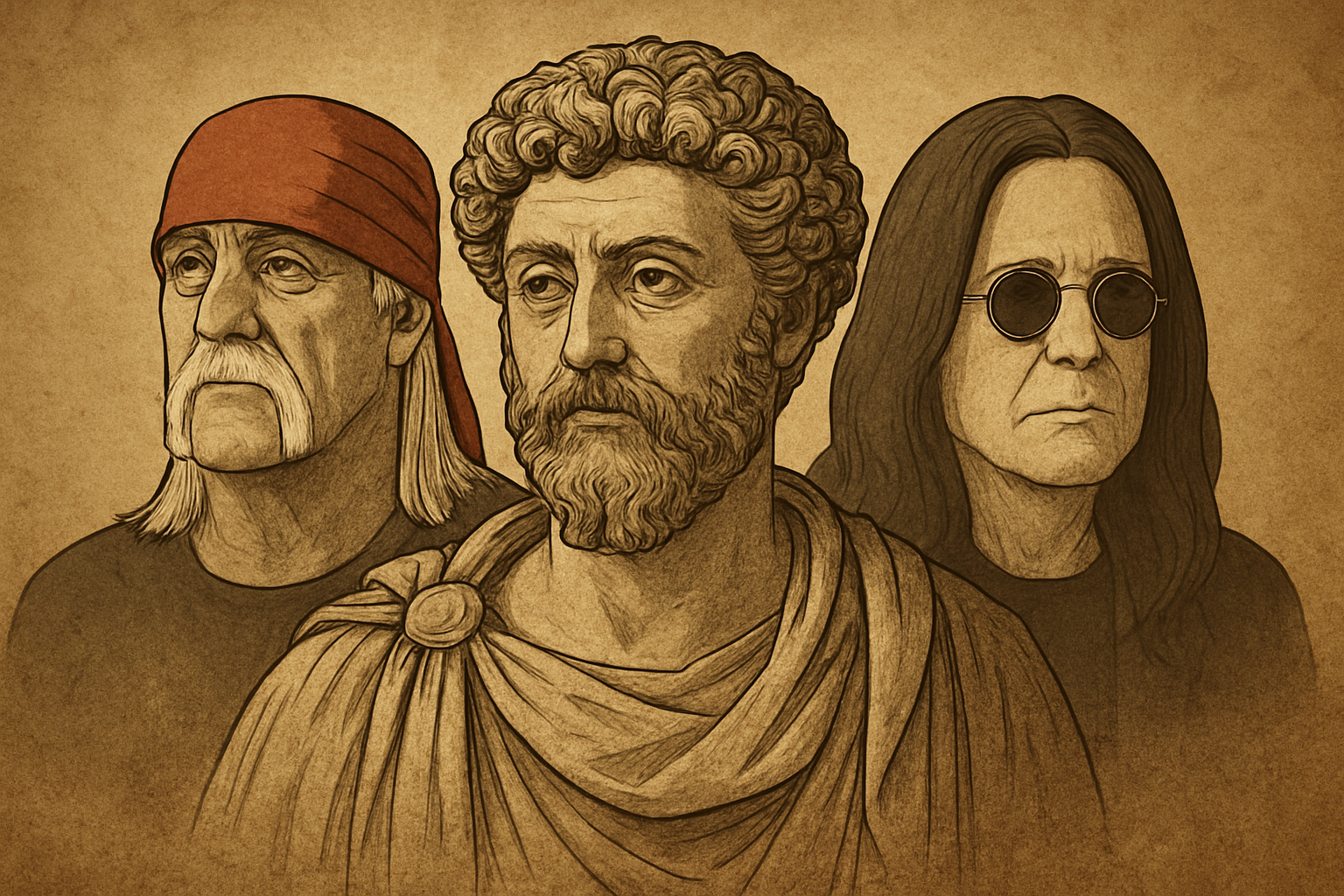

The ancient Stoic reflections resonate just as strongly in our own time. Not long ago, two major celebrities died in the same week — Ozzy Osbourne and Hulk Hogan — names that for decades carried an aura in the global imagination. The internet erupted with comments that all seemed to chant the same refrain: “everyone keeps dying.” What most people lack is a philosophy to meet such inevitability with calm. The Stoic response to this cry of protest is simple: If it were not meant to be this way, it would not be this way. To rage against it is to rage against reality itself.

Marcus’s old lament resurfaces here: the companions of our age are slipping away, and the procession will not stop until we join them. Few today care much for “the funeral carriage passing by,” and yet every carriage is a reminder of our own place in the same line!

I saw this truth in a quieter setting. Richard, the oldest employee in a furniture store where I once worked, sat slumped in a chair, eyes fixed on the television as it announced Queen Elizabeth’s death. His silence carried something heavy — the look of a man who had lost not just a monarch but a piece of national identity that had been present since his youth. In his posture I saw what the Stoics meant: whether it is the passing of an icon or the fading of a colleague, impermanence is always near.

The Stoics counseled memento mori — remember death. This was not meant to darken the spirit but to strip away illusion. To contemplate mortality is to stop clinging to what was never ours to keep. It is to see clearly the difference between what belongs to Fortune and what belongs to us: our character, our choices, our present moment.

Marcus’s words — “How many in whose company I came into the world are gone away already!” — remind us that we too are temporary travellers. But far from despair, this realization should rouse us to live with humility, courage, and care. Death is certain, the hour unknown; what matters is how we meet each day, how we treat those who walk beside us, and how prepared we are to join the countless multitudes who have already gone before.