If you study Buddhist philosophy, there’s this Pali term that’s thrown about often, but it’s not a trivial term, but a central concept to the entire philosophical framework. The term I’m talking about is the word dukkha. By the way, Pali is what the Theravada Buddhists regard as the language the Buddha did speak in.

Dukkha is popularly thought of as just only meaning suffering. That view is wrong, there is more to the word than that. Just to clarify, suffering commonly means physical and mental forms of unpleasant and aversive sensations. To give examples of both, physical suffering can be: skin boils, arthritis, cancer, autoimmune diseases or accidents e.g. and mental sufferings can be: anxiety, stress, depression and frustration e.g.

Don’t get me wrong, physical and mental forms of pains and hardships do come under the definitional umbrella of dukkha, but that’s not the whole picture. Dukkha when translated into English is an ambiguous term, meaning a term or concept with more than one meaning. It’s translations are: suffering, anxiety, stress, discontentment, dissatisfaction. It’s all these translations rolled up into one carpet that make up dukkha. The latter two meanings in bold is what gives dukkha its deeper meaning and is the focus of this article.

More than just painful sensations

You may in your life not be undergoing physical sufferings like: skin boils, arthritis, cancer, autoimmune diseases or accidents.

You may in your life not be undergoing mental sufferings like: anxiety, stress, depression or frustration.

You may in your life be an all-round healthy person, who is safe, who is financially secure and free of mental perturbations; because there are basically no external problems.

Yet there is still this dissatisfaction, this dukkha; why? This is because we are unsatisfied and unfulfilled, we go on and ask from life things which it cannot always give us. Thwarted by the disappointments of our endeavours, more and more dukkha heaps up, or, in other words, there is further prolongation of dissatisfaction and unfulfillment. Typically people try to alleviate this state by pursuing something more, for example, if you say: ‘I feel that there is something missing in my life’ then you’re the quintessential example of dukkha. It’s like some special kind of boredom. So what is the ultimate cause of this dukkha? The cause of dukkha is birth! The buddha didn’t intend on being pessimistic when he stated this, he was coming from the perspective of cause and effect because to even be capable of dukkha there has to be a self or a sense of self to experience it.

More discontentment!

Ajahn Chah, the Theravada Buddhist monk, teacher and abbot of Wat Nong Pah Pong monastery, made an observation on university students: “Many people who have studied on a university level and attained graduate degrees and worldly success find that their lives are still lacking. Though they think high thoughts and are intellectually sophisticated, their hearts are still filled with pettiness and doubt.1”

Here are some more examples of dukkha as discontentment and dissatisfaction:

- Dukkha is being in state of wanting for the craved object

- Dukkha is getting the object what one wanted but then finding out it did not satisfy enough

- Dukkha is meeting your famous celebrity role model only to find out that in person they are a disappointment. Chah once said: ‘hearing a person’s name is different from meeting him’

- Dukkha is addiction to things like smoking cigarettes, it will never be enough no matter how much one smokes

- Dukkha is the underlying dissatisfaction of not living up to overarching societal standards

- Dukkha is the disappointment you felt when leaving the cinema after watching a hyped up film (I’m looking at you Disney’s Star Wars)

I recently asked my friend over the phone, who watched that Rise of Skywalker film at the cinema, if he got lasting contentment from watching it. So, did that film fill that gaping void of dissatisfaction from before? His reply was a grunt and a wish to change the subject; I guess it did not satisfy one jot.

The Buddha knew about things like this

Before his enlightenment, the Buddha was known as Siddhartha Gautama, a privileged pampered prince kept in a palace paradise by his father, King Suddhōdana. He knew from first-hand experience that one can be lavished in opulent conditions and having everything served on a gold platter and yet however still be dissatisfied.

The teaching from the Buddha can cast light for us here (see references2.) The uninstructed worldling is someone who does not know the buddhadharma (Buddha’s teachings) who typically is attached to conventional ideas of happiness. In response to painful feelings, the uninstructed worldling seeks delight in pleasure; the reasons being that he does not know of any escape from painful feeling other than sensual pleasure. It is a tactic many of us employ to distract the mind from mental perturbations. Separation from desired objects or situations, especially when our attempts to covet them are frustrated, are dukkha. Union with undesired objects or situations are dukkha also.

Contrast this with the instructed noble disciple, who is learned in the buddhadharma, who has his own from pain other than sensual pleasure ‘if he feels a painful feeling, he feels it detached.’ The worldling feels pleasure and pain attached while the noble disciple feels pleasure and pain detached. Here’s another example which separates the two:

“while the worldling is elated by success in achieving gain, fame, praise, and pleasure, and dejected when confronted with their undesired opposites, the noble disciple remain unperturbed.”

Conclusion

Our dissatisfaction with our life originates within us, our minds are the only thing responsible for this. Does our craving mind have its limits? well to answer that, no it does not have limits. We must come to the realisation that since the mind is changeable, so are its craving for novel sensual gratifications or kamatanha:

“Our sense-desires constantly ask for more by way of worldly objects, like a pack of voracious dogs it can never have enough… This disorderly mob of the senses can never reach satiety, not by any amount of sense-objects; they are rather like the sea, which one can go on indefinitely replenishing with water.”3

In Buddhism, no object have give us lasting contentment because both the mind and the object are changeable. There are many more examples I can give but these two examples illustrate the point: either the mind changes, because it may get bored with the object, prompting it to crave for other baubles or the object itself changes, because it’s subject to wear and tear due to the ongoing effects of entropy.

“People become neurotic, why? because they don’t know! They just follow their moods and don’t know how to look after their own minds”

When I read this statement by Ajahn Chah, spontaneous ideas arose in my mind of the implications of this seemingly simple statement. When people follow their moods, in this case bad ones, they are continually reproducing it. The mood is replaced by other moods by an interruption of the mind’s tendency towards change. For example, if we find ourselves in a bad mood it does not last forever because something else will alter the state of mind.

If we wish to avoid discontentment we should follow the wisdom offered by philosophies like Stoicism and Buddhism. We must tend to the mind like a farmer tends to his ox, should the farmer be distracted or goes to have a kip under a tree, the ox will eat the field of crops and that’s goodbye to the harvest! the good farmer is mindful of the ox by keeping an eye on it, he knows exactly when to discourage the beast from the crop by disciplining it. The same principle goes for the mind, if we are not mindful of its shifting and changing states like the desert sands, then we will only make trouble for ourselves in heaping up dukkha. Mindfulness is key.

“The serene and peaceful mind is the true epitome of human achievement. – Ajahn Chah”

References:

1. Kornfield, J. (1985). 1 Understanding the Buddha’s Teachings, The Middle Way. A Still Forest Pool. Third Quest Printing. pp. 6

2.Bhikkhu Bodhi. (2005). ‘The human condition, 2. The tribulations of unreflective living’. In the Buddha’s words. Wisdom Publications Inc. pp. 31-33

3.Conze, E. (1959). ‘Meditation, 3. The progressive steps of meditation, the restraint of the senses’. Buddhist Scriptures. Penguin Books. pp. 103

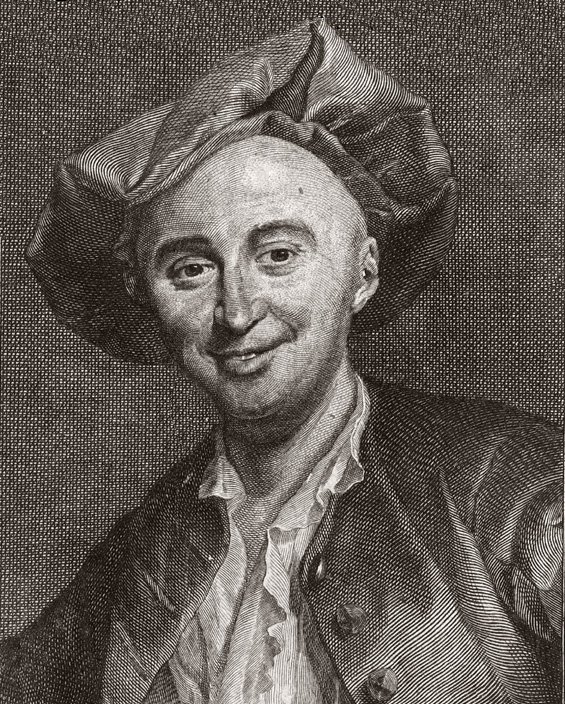

[…] 7 mins agoThe dissatisfied Viking 5 days agoThe humble honesty of a Roman emperor 1 week agoBuddhist philosophy – Exploring Dukkha as more than just suffering 3 weeks agoSelected La Mettrie Quotes… 3 weeks agoStaring at Lions – What is […]